Nextdoor Censors Are Hard at Work Hiding the Truth from Local Readers

You should know, there are interests in and around Forsyth County who do not want you to read my articles. Recently, another Substack article of mine, one entitled, “Commission Chairman Desperate to Avoid Answering Questions,” was censored, removed from view by Nextdoor. The reason the Nextdoor censors gave me was to allege that I engaged in “personal fundraising.” First of all, if you look at the Nextdoor guidelines, personal fundraising is not prohibited. And if you are a subscriber to my Substack, you also know that everything I publish is free-of-charge. I do not write these articles to raise funds. I write these articles to raise awareness, for readers to better understand the political environment in which they live, whether my subject might be state, federal, or local politics, or even geopolitics. The following is the first paragraph of the censored article. In it, I deal directly with the fact that my articles are free to anyone who is interested and are not a means of fundraising.

Because what you see is the very first paragraph of the article, and because that paragraph directly counters the grounds on which Nextdoor removed it, there is no excuse for any so-called “moderator” to hide it from view for the reason given. And the same goes for this article. The post in which the link above appears does not violate the published Nextdoor standards, and the nameless, faceless Nextdoor censors know it. Whether they will unhide the article, I do not know. Whether they will hide this article, I do not know either, which is why I tell you again, that subscribing to my Substack is always FREE-OF-CHARGE, and if you do not want to take the chance of missing the information I publish, your only real solution is to subscribe. I make no money at this. You can subscribe by clicking on the green box below and you can unsubscribe any time.

The “Easement-for-Resolution” Quid Pro Quo Your County Government Wants to Hide

I write this article from the standpoint of a county taxpayer of 38 years. I have seen many changes in Forsyth County from my perch two miles from downtown Cumming. I was pleased when we finally got a Blockbuster store. I was pleased when Ingles moved in a mile away. We no longer had to drive to Alpharetta to go grocery shopping.

Obviously, many things have changed in 38 years, and I understand progress is inevitable. But one matter that has changed about which I cannot console myself is the extent that local government now inhabits daily life in Forsyth County. And that would not be so bad except that those who occupy our elected offices have largely forgotten what public service is. In recent times, these individuals have taken to banding together, creating an informal, however highly politically-charged “Club.” The Club’s purpose is to occupy every elected office in the county, and thereby control every possible decision concerning the future of Forsyth County. Regardless what party designation these Club politicians might ever claim, the bottom line is that, by banding together they can control the future of Forsyth County, possibly in illicit ways, ways that promote their own self-interests, for example. These Club members promote each other’s races. They hand each other political contributions. They use the same political advisors and campaign consultants. Once elected, they largely abandon the very purpose of elected office, which is to represent the people who elect them. And the results are governmental decisions, based in considerations that defy the public interest. The one about which I write today, is one of those decisions.

Thus, what you are about to read may seem confusing. But it is only confusing because I am reporting about confused people doing confusing things. What is hard to swallow is the fact that these confused people are doing all those confusing things while running our county government. So, if you become confused reading about these people, relax, it’s not you. It’s them. You haven’t lost your mind. If anyone has lost their sanity, it is those about whom I write and who happen to be in charge of your county, and, importantly, your county tax dollars.

The story you are about to read is true. As things sit, your Forsyth County Government is being run by some desperate people who made a huge mistake with taxpayer money. And now they are trying to figure a way out of a mess of their own making, and its not going to be easy.

I’m not saying anything they have done is necessarily illegal, well not saying that YET. But what they have done is mind-boggling, and a certain group of them has been either trying to conceal the problem, or cover up the problem for almost two years.

A Review from Last Time

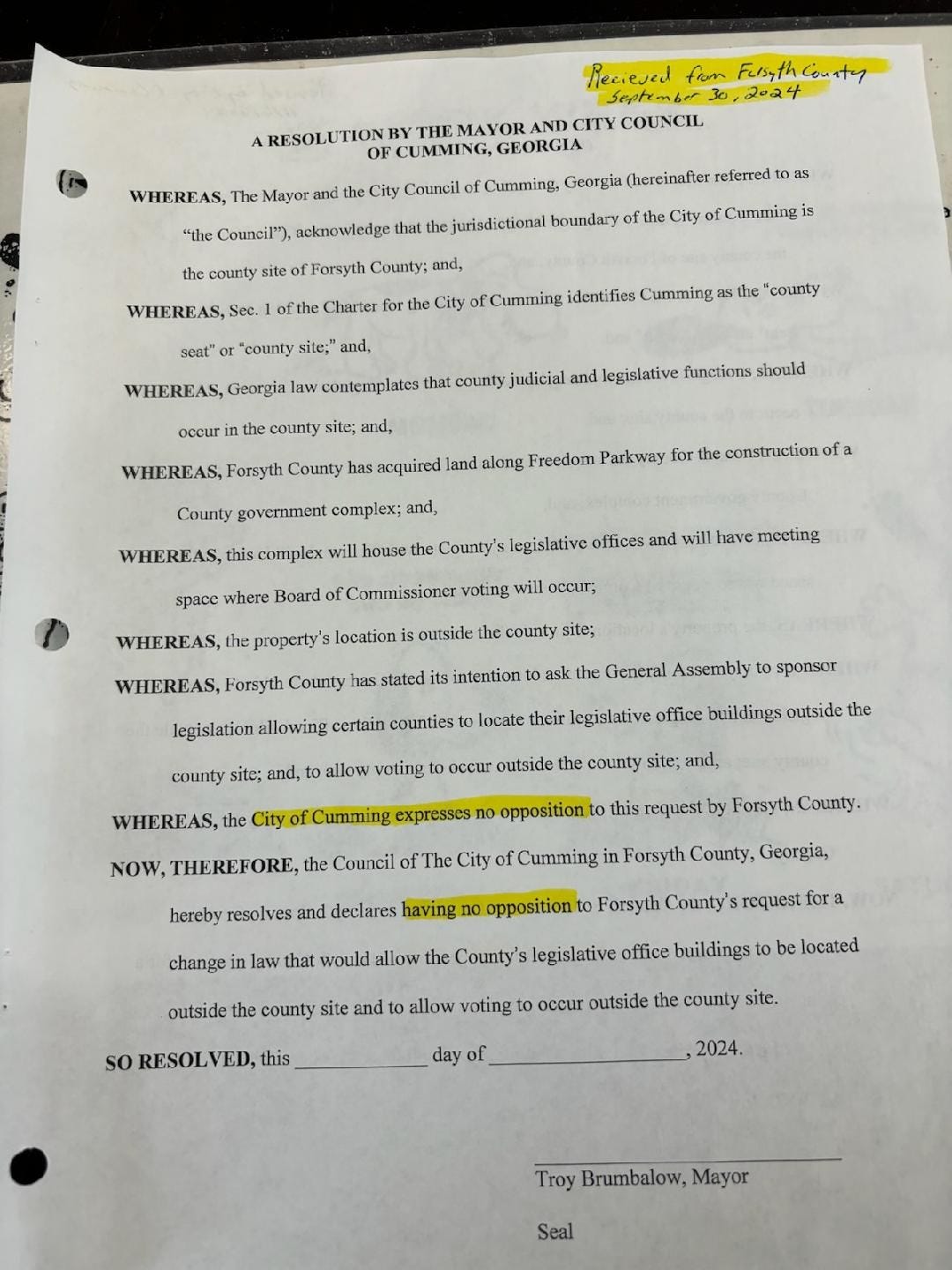

If you can count yourself among thousands fortunate enough to gain access to my previous article, before it might have been unjustly removed by one of your favorite local social media censors, you will remember that City of Cumming Attorney Kevin Tallant received a resolution, written and proposed by Forsyth County Attorney Ken Jarrard, for the Cumming City Council to consider signing.

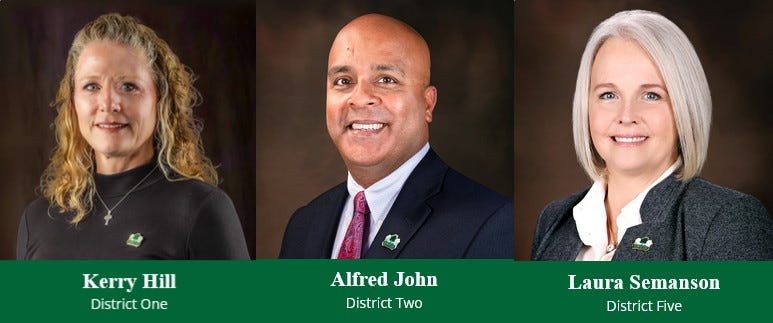

The purpose of that resolution stemmed from the fact that last January, three county commissioners, Alfred John, Kerry Hill and Laura Semanson, did a very confusing thing. In a 3-2 vote, those three commissioners decided to spend what would become $114 million of your tax dollars, contracting to build a new administration complex. All told, apparently the cost of the new facility is now $134 million. That’s not so confusing. The confusing part is that the building now well under construction is located outside of the county seat of Cumming, and each of those three commissioners knew when they voted that Georgia law prohibits the county commission from officially acting in that location. Why would those commissioners do that? Well, that is a $134 million question. As I write, I will attribute that decision largely to a state of personal confusion existing in the minds of the three by whose votes the decision was made. But I also recognize that at some point, the confusion I attribute as the reason for their unexplainable votes could easily give way to intrigue, meaning we could discover some ulterior purpose, either theirs or someone else’s. In other words, one can only be so stupid before one becomes purposely stupid. But the jury is still out on all that.

And now we see those same three commissioners in a state of confused desperation to discover a way out of a situation they, themselves, created by their votes last January. The resolution sent to the City of Cumming was one more attempt at throwing spitballs at a wall and hoping one will stick. To refresh your memories, the resolution in question can be seen below:

What the New Admin Project Cost You

To give you an idea of the magnitude of the cost of the new admin complex, the project underway on Freedom Parkway, including $5.4 million for the land cost, and various costs associated with the concept and plan development, is costing an average family of four in Forsyth County almost $2000. That out-of-pocket expense is being paid from property tax receipts. I do not know how many property owners there are in Forsyth County, but it is far fewer than the number of residents, making that average cost actually much higher among those required to pay it. Renters, however, absorbed that cost plus a landlord markup, so no one is really exempt. And that is just the cost for constructing the buildings. There are furnishings, computer systems, an entire gamut of costs totaling up to many millions, not to mention staff hirings to fill all the new seats. So, $2000 per household is just an approximate starting point.

The question I asked in my censored Substack article was to discover who among those at Forsyth County Government approved Mr. Jarrard to spend county taxpayer dollars to draft a resolution for a outside governing body, the City of Cumming, to consider. After all, the city has its own attorney and can pay him to write resolutions if they perceive the need. And the answer to that question is also what Forsyth County Commissioners Cindy Mills and Todd Levent wanted to know, who for several weeks placed discussion items to obtain that answer on consecutive meeting agendas, only to have Commission Chairman Alfred John pass consecutive motions to postpone those discussions until January, at which time the retiring Mills will no longer be on the commission.

Twice stymied by the chair postponing what could be an important and revealing discussion, thankfully for the taxpayers, Mills and Levent persevered. For a third meeting they offered the same agenda item for discussion, this time at the November 26 commission work session. Pressured by public exposure of his efforts to disallow the discussion, this time Chairman John did not move to postpone, obviously forced against his druthers to allow the conversation to occur. As you will discover below, statements by certain actors involved with generating the resolution reveal an apparent effort to hide the facts surrounding its proposal to the City of Cumming.

The November 26 Commissioner Work Session

At the appropriate time during the meeting, the chairman asked Commissioner Mills to begin the discussion, which she did:

In the video, Commissioner Mills mentioned the term, “quid pro quo,” a Latin phrase which literally means, “this for that.”

Once Commissioner Mills introduced the discussion purposed to discover the origin of the resolution sent to the city, County Manager David McKee immediately asks to speak to the facts surrounding the resolution submission. Rather than dealing with the resolution, however, McKee’s remarks center squarely on an easement request made by the city attorney a few weeks prior, the nature of which I outlined in my previous Substack article linked above. McKee’s remarks, if true, would effectively decouple any consideration suggesting that the easement request would have anything to do with the resolution, vacating the likelihood of a quid pro quo becoming planted in the public mind. Here is what Mr. McKee said:

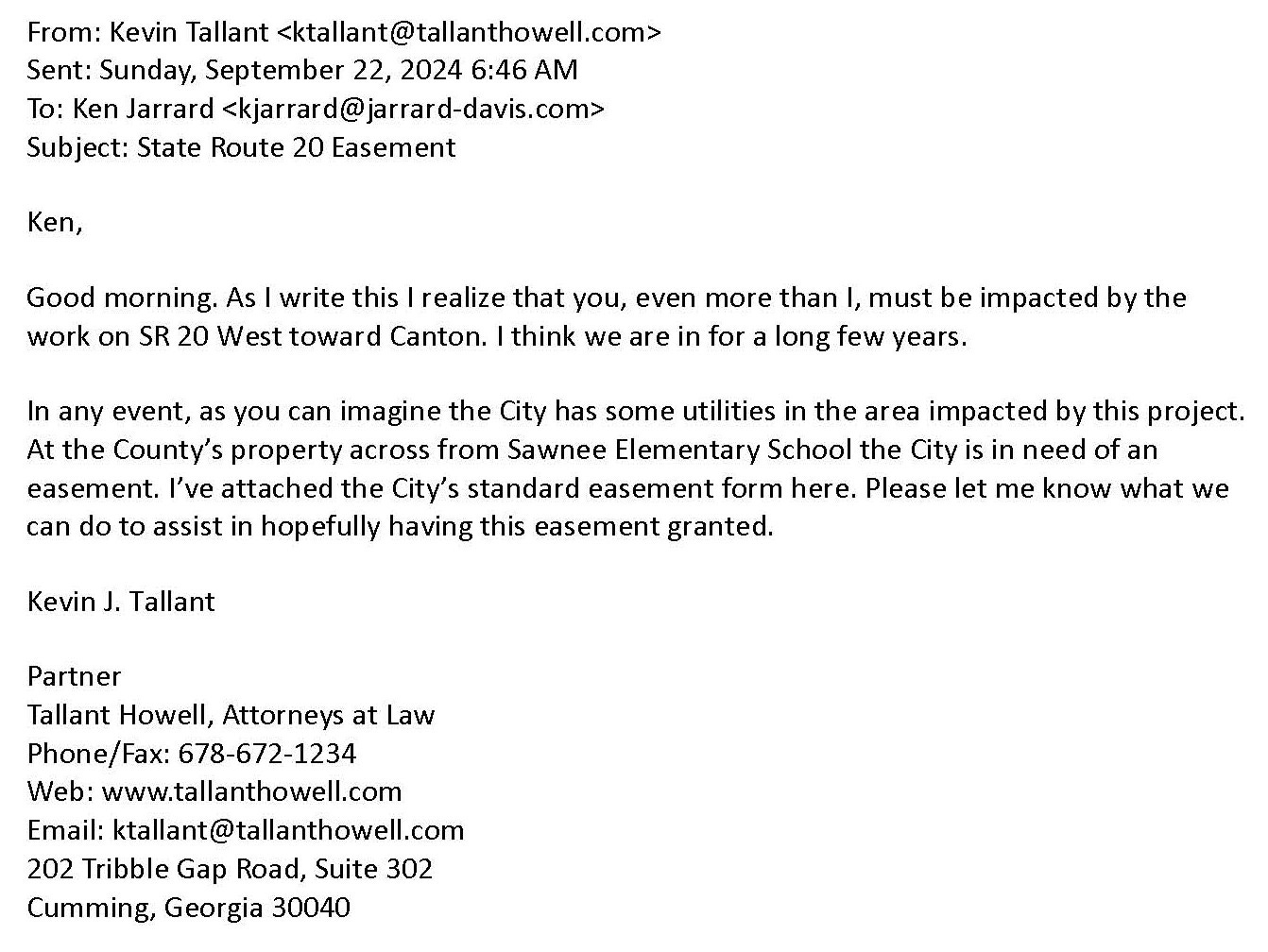

Unfortunately for Mr. McKee, that which the county manager presents so emphatically as a “fact” is disputed by the available evidence, that statement of his being the first among several apparent mistakes made by McKee during the work session meeting. The requested easement for the city waterline was sent by city attorney Kevin Tallant, received via email on September 22, by county attorney Jarrard, the individual sitting to McKee’s left. The request was not sent via “snail mail” received along the way by certain unidentified county personnel, as McKee suggested. Below you will find the emailed easement request, the proposed easement requirements being attached to this message.

And even though the county attorney obviously would know certain “facts” McKee related were highly suspect and/or erroneous, at no time during the work session did Mr. Jarrard move to correct any of McKee’s statements. Thus, anyone listening to the county manager might easily believe that the easement requested by the city was not a part of any deal offered the city in exchange for signing Jarrard’s resolution.

Digging his hole still deeper, county manager McKee then asserts that neither he, nor anyone else involved, ever “even looked at it,” referencing the easement request. Notwithstanding his apparent lack of concern for a legitimate city request, the effect of the county manager’s statement is to further decouple any perception of a “quid,” meaning the signed resolution, being offered in exchange for a “quo,” meaning the easement.

In the above video, Mr. McKee insists that Mayor Troy Brumbalow “had no issues” with the county doing its business outside of the county seat of Cumming. That statement will become almost his mantra, the county manager repeating it more than once during the meeting. Importantly, McKee’s insistence that the mayor was indifferent as to the location of the county admin building would become the major assumption on which county attorney Jarrard will propose to rely, and which Jarrard will insist motivated the idea of drafting the above resolution for the city to consider.

Upon hearing McKee’s claim, Commissioner Mills then probes the county manager’s claims, obviously hoping to better understand what was really said to him by the mayor and when Mayor Brumbalow may have said it:

Thus, when asked about the timing of his conversations with the mayor, McKee answered that he could not recall whether the conversations with Mayor Brumbalow occurred before or after three members of the county commission, Alfred John, Kerry Hill and Laura Semanson, voted by a 3/2 split of the commission to effectively remove $6 million from the city’s SPLOST revenues over the next six years. We should question how Mr. McKee could have answered that question truthfully, apparently not remembering whether the conversations with Brumbalow occurred before or after the SPLOST vote. That is because the two referenced meetings with the mayor were for the purpose of preparing both sides for that very vote.

Obviously, the meetings with Brumbalow occurred before the July 18 commission vote, at which time the county commission surprised everyone by rejecting the county’s own proposed SPLOST agreement with the city. Because McKee was the county’s “point man” on the SPLOST negotiation with the city, the county manager should have known the answer to Commissioner Mills’ question, although he claimed he could not readily remember.

According to Mayor Brumbalow’s records, he and McKee met twice on SPLOST, the first meeting at City Hall on March 19th of this year, at 4:30 in the afternoon. According to the mayor, the subject of that meeting was solely to kick off a conversation concerning a prospective SPLOST intergovernmental agreement (IGA) between the county and the city. According to the mayor, the admin building was not discussed at that meeting and the two men agreed that the city would put together a “wish list” of SPLOST projects and cost projections, and schedule a next meeting to discuss the SPLOST IGA revenue split.

Also according to the mayor, the next meeting occurring on May 8th, this time during breakfast at the Station House. According to Mayor Brumbalow, it was during that meeting that Mr. McKee brought up the state law and the legal restrictions against the county commission voting outside of the city limits. When McKee asked the mayor whether he cared about the location county meetings would be held, Brumbalow recalls his response being that he “could care less” where the county votes, whether in Cumming, Coal Mountain or any of a few other locations he identified. But the mayor also qualified his personal opinion, unreported by McKee to the commissioners, informing Mr. McKee that he had no authority over that issue one way or another, that the county’s problem was a state law, and that all authority for city policy resides in the city council, not the mayor.

Regardless who might be more correct in remembering the two conversations, during the work session county attorney Jarrard would use McKee’s avid insistence of the mayor’s indifference as the foundation necessary to justify offering the city a resolution expressing non-opposition to the commission voting outside the county seat. Unless the city might agree to such a resolution, it would be practically impossible to gain unanimous support among the Forsyth County state delegation to sponsor a bill to change the offending state law and associated local ordinance during the upcoming general assembly. If a resolution such as described ever had a chance for acceptance by the city, any such plan would likely prove dead-on-arrival after a commissioner’s meeting last July, during which the three majority members of the county commission, John, Hill and Semanson, figuratively back-stabbed the city, failing at the last minute to agree to the county’s own SPLOST IGA proposal, a proposal already approved by the city, that maneuver being the one referenced by Commissioner Mills in the above video. And that is why Commissioner Mills asked McKee whether the mayor expressed his perceived indifference “before the vote was made to take six million away from them.” McKee refrained from answering that question, one to which he should have known the answer, in the end merely repeating his mantra, “Multiple times there was no issue.”

Still not finished with his apparent purpose, to achieve an even larger logical chasm between the easement requested by the city, and the resolution requested by the county, in the following video segment, Mr. McKee indicates that the county’s diligence in understanding and acting on the city’s easement request was a complicated matter being worked through by county staff at the time the resolution was sent, a statement which, if true, would effectively insulate the easement from being a part of any deal proposed to go along with the resolution county attorney Jarrard drafted and proposed to the city.

McKee says, “Before we go entertain this easement request to the board…why don’t we go ahead and see if the city will shake loose a resolution of which they don’t have an issue with, right?” McKee’s version of events thereby effectively severs any reliance between the city’s easement request to the county, and the county’s resolution request to the city. According to McKee, the easement request made by the city would effectively stand on its own merits at some future date once his staff had a chance to look at it to understand what it all meant and once the easement request might survive the normal easement request rigors. In so stating, McKee grounded his position that no county effort was being made to leverage the value of the easement request to influence the city council’s adoption of the resolution. In other words, according to David McKee’s statements, a quid pro quo involving the easement request and the resolution Mr. Jarrard sent to the city would be virtually impossible because the county had not yet performed its due diligence on the easement when the resolution was sent.

Almost gratuitously, in the above video McKee proposed the possibility that the city council never brought Jarrard’s resolution up as business during an official meeting, the resulting natural conclusion, if true, being that Mayor Brumbalow, and/or the city attorney, would have revised the resolution privately, without council authority, and sent it back to the county. As you will see below, none of Mr. McKee’s proposed version of events, nor his implications about the returned resolution document, would prove true.

Meanwhile, Over at the City

Before we analyze county attorney Jarrard’s statements on the matter, let’s look at the events happening over at the city. Cumming City Attorney Kevin Tallant is the individual who received the resolution drafted by county attorney Jarrard. Accordingly, if the city would sign the resolution, Tallant understood from Jarrard that the county would grant the requested easement. In the video below, Mr. Tallant presents the “quid pro quo,” speaking to the Mayor and Cumming City Council members during a council meeting held November 6th.

Once Mr. Tallant presented Mr. Jarrard’s resolution, in the video segment below Mayor Brumbalow asks the city attorney to clarify a few stipulations, and afterward asks for a motion and a vote to revise the resolution and send it back to the county.

Remember, according to county manager McKee, speaking at the November 26th county work session, the easement request was in no way coupled to the resolution. According to the county manager, the easement was still being analyzed by staff when county attorney Jarrard sent his resolution draft over to Tallant. Although that is what Mr. McKee indicated to the commissioners, you just heard the Cumming City Council entertaining the county’s resolution, as Jarrard had coupled it to the easement requested by the city, doing so in the form of a what Mr. Tallant would describe a “quid pro quo.” One might question whether Mr. McKee knew what Mr. Jarrard was doing with the resolution at the time. Jarrard, however, made no effort to correct the errors of McKee’s work session statements when he obviously had the chance, which lends credence to the prospect that the two cooperated on an overall, composite narrative each helped to present during the commission work session.

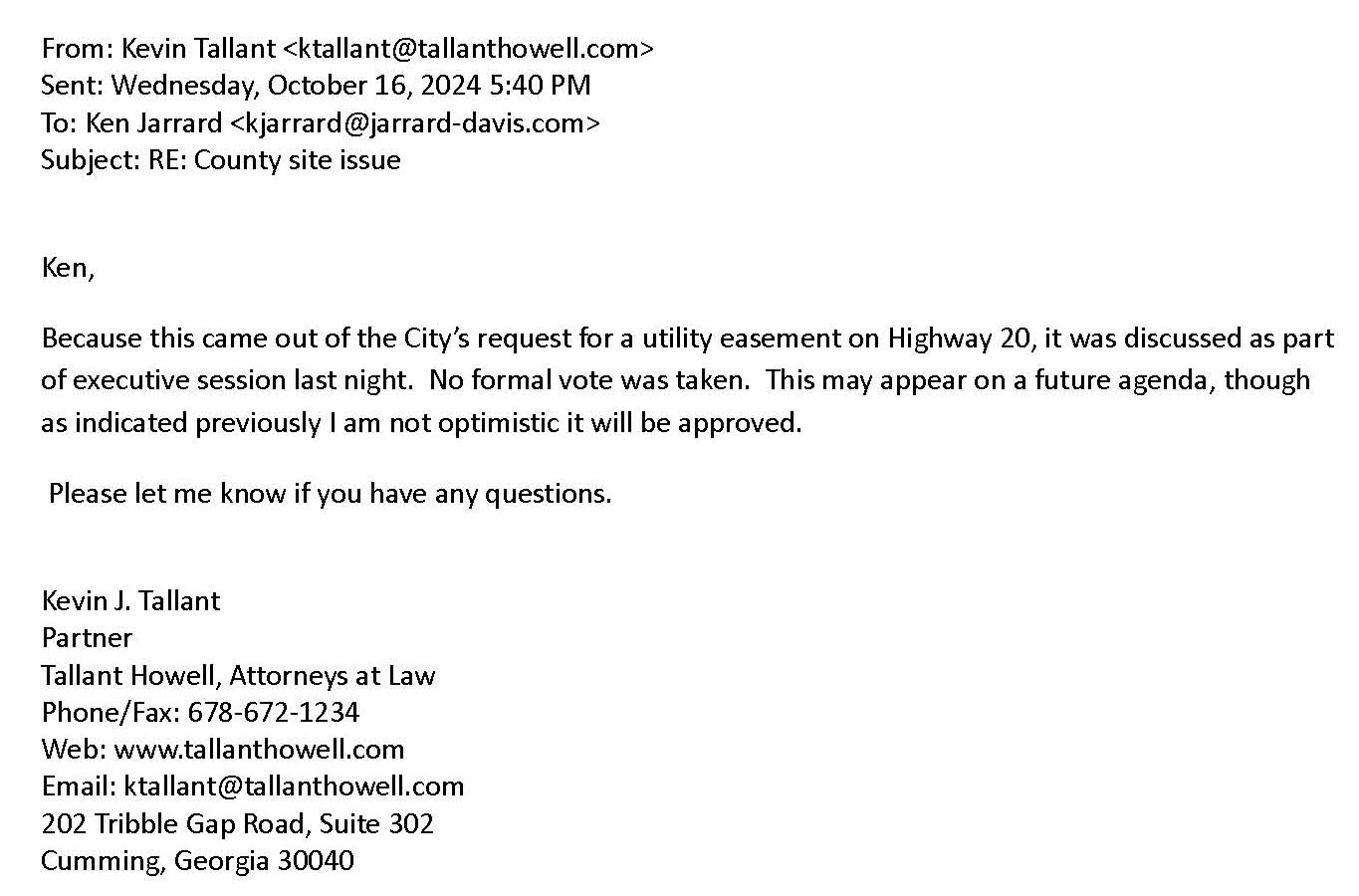

On September 22nd, City attorney Tallant emailed the easement request to county attorney Jarrard. Jarrard responded, transmitting the resolution to Tallant eight days later on September 30th. According to Tallant, Jarrard proposed the deal, exchanging one for the other during a phone call. The county would grant the city’s easement request, but only IF the city would sign the proposed resolution. Jarrard did not put the quid pro quo deal in writing. Although there is no recording to validate what was said during the phone call, there exists corroborating evidence that a quid pro quo had been proposed by Jarrard during a phone conversation in conjunction with his sending the proposed resolution. That evidence is an October 16 email response from Tallant to Jarrard regarding the “County site issue.” In that email, Tallant speaks to the deal proposed by Jarrard, referencing the subject matter as “County site issue,” meaning the resolution, which “came out of the City’s request for a utility easement on Highway 20.” In so doing, Tallant memorialized the two considerations together as a deal, a quid pro quo proposed over the phone by Jarrard to the City of Cumming, a deal which Tallant would inform Jarrard, he was “not optimistic it will be approved.”

County Attorney Jarrard’s Statements to the Commissioners

Knowing what we now know, let’s go back to the November 26 commissioner work session and listen to what county attorney Ken Jarrard had to tell the commissioners concerning his role in preparing the resolution he sent to the city:

Mr. Jarrard makes it clear, he is the one who drafted the resolution sent to the city. We knew that. But, notice he said nothing about the city’s easement request being coupled to that resolution. Instead, he accepted Mr. McKee’s narrative that the easement was being dealt with in the background of the county’s approval process, county staff apparently still performing due diligence to understand the request even as Jarrard addressed the commissioners, thereby, again, effectively isolating the easement request from any resolution Jarrard proposed to the city.

Cryptically, Jarrard prefaced his remarks claiming to be at a “disadvantage” among the group assembled. He explained that his disadvantage stemmed from a belief that he shares an “attorney-client relationship” with each of the commissioners, and thus, he was “not prepared to speak about the things being talked about in this session.” He explained, however, that commissioners could wave that privilege should they choose, an interesting way to introduce a discussion concerning a seemingly unrelated resolution he sent to the city. Mr. Jarrard seemed to say that he could not volunteer certain information then and there, which, if true, could only have therefore been received from one or more of the commissioners, without them first waiving attorney-client privilege. Of course, no one spoke up to take advantage of that opportunity. Then, in the video Mr. Jarrard spoke just as mysteriously, stating his belief that the information with respect to the county site was “out,” waving his hand perhaps in such a way as to represent the outer cosmos, having received that information long before the January vote to accept a $114 million bid to build the new admin building. Note, he did not say to whom that information had been given, only that the information was, “out” somewhere in the universe. So, what might all that confusing, cryptic language actually mean?

I confess, I do not know with any level of certainty. But it sounds as if the county attorney was saying that he, himself, could not volunteer certain information pertaining to the subject matter being discussed at the meeting due to an attorney-client relationship he shares with one or more of the commissioners seated at the table. He seemed to say that it would be up to those commissioners, or perhaps one in particular, to waive that privilege for him to be able to volunteer information he might know on the matter, but that he, as their attorney, could not volunteer that information without client permission. I do hate to speculate here, but, frankly, when individuals offer such vague discourse as did Mr. Jarrard in this instance, they invite others to make educated guesses as to what they mean.

Regardless what the county attorney may or may not have meant in the above segment, here is what we do know. During the last two years that the new admin project was on the drawing board, with regular discussions happening among the board members during meetings, the only commissioner who admits knowledge of the legal problem with voting at the Freedom Parkway site during that entire time, is Chairman Alfred John. He did so the night of January 18 when the commissioners voted to approve the building contract.

It is now my opinion that Chairman John somewhat innocently misspoke as to the time frame during which he learned of the legal problems with the admin site. Rather than the time frame being “late 2021 or early 2022,” I expect he meant “late 2022 or early 2023.”

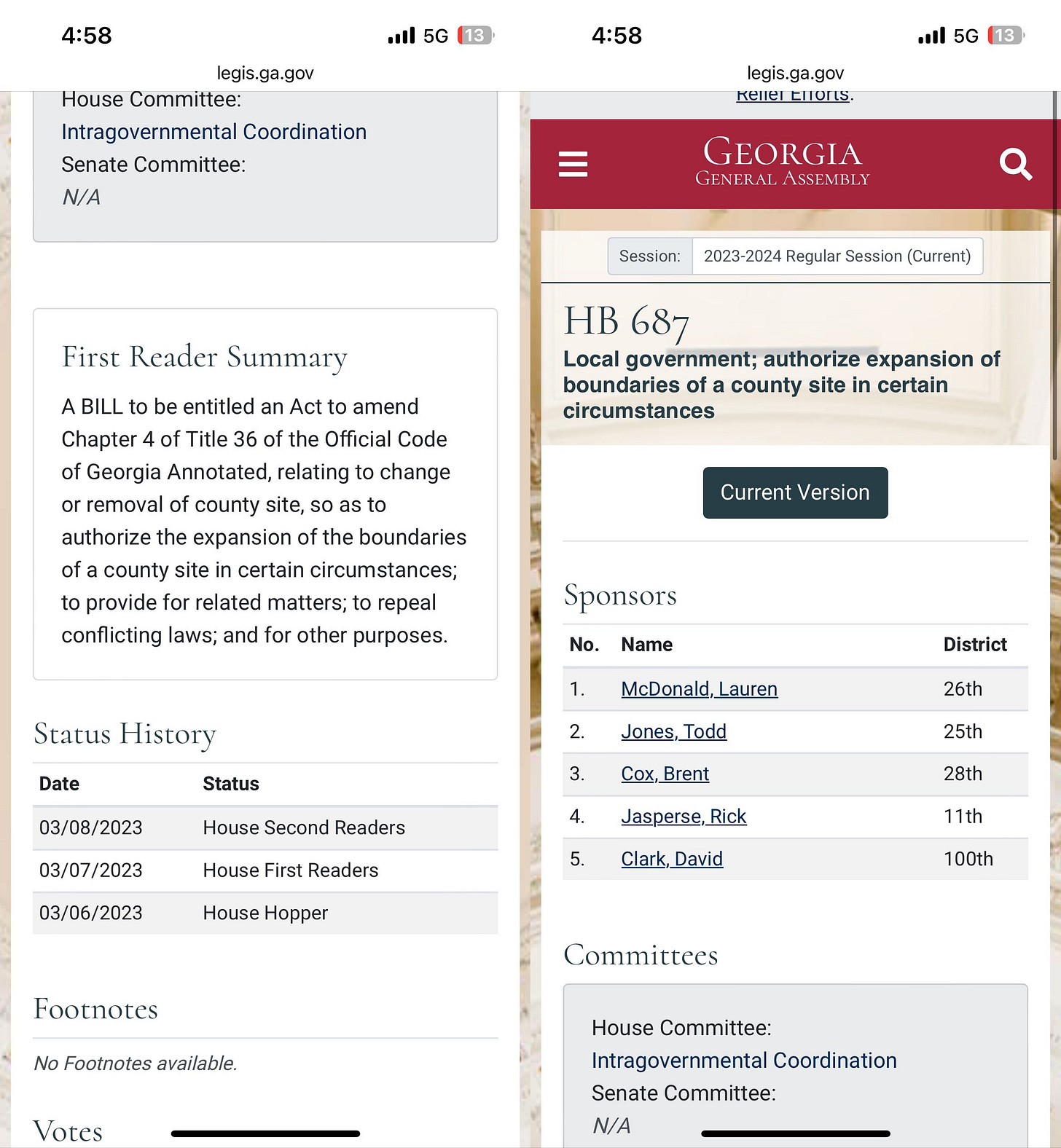

We also know that county manager McKee understood the legal problems in early 2023 because in the video below he shares that he asked Representative Lauren McDonald to submit a bill to solve the problem, and we have a public record that Rep. McDonald dropped that bill in the hopper on March 6, 2023. In the video McKee insists that he made the request of McDonald on the same day McDonald dropped the bill in the hopper, which merely shows that McKee made a somewhat inconsequential mistake remembering his dates, obviously having made the request of McDonald much earlier, figuring time necessary to understand and write the bill after McKee’s request. Notably, however, Mr. McKee insists that his attempt to change the law governing the location of county commission meetings occurred AFTER the vote to accept the $114 million contract was made. That was not correct, and as Commissioner Mills attempts to interject the correct time frame into the conversation, McKee argues her into silence.

Had Mr. McKee’s time frame of events been correct, those facts could have cast him in a much better light, having innocently learned of the problem AFTER funds were committed to contract. Commissioner Mills, however, was correct when she said, “That’s a long time before the vote was taken next year in January.” McKee obviously would accept none of that. However, the evidence strongly suggests that the county manager knew about the legal problem for ten to twelve months prior to the vote to commit funds to contract was taken on January 18, 2024.

We also know that Rep. McDonald would have needed the legal specifics and analysis necessary to write the bill McKee asked him to submit long before McDonald dropped the bill in the hopper on March 6, 2023. That information would have had to come from an attorney versed and privy to the problem, a conclusion strongly suggesting county attorney Ken Jarrard knew about a serious legal problem associated with building the county admin project outside of the Cumming city limit, along with commissioner John and county manager McKee, in early 2023.

Now, in the following few remarks, Attorney Ken Jarrard proposes his rationale for conjuring the authority necessary for him to spend county tax money to draft a resolution designed not for the county that pays him, but instead for the City of Cumming to consider. Below, hear the rationale the Forsyth County attorney proposes for you and the commissioners to believe:

Yes, obviously it’s a problem. But understand the deeper context of Mr. Jarrard’s remarks. In that video, the county attorney expresses his belief that once the board decided to spend “$100 million dollars” of taxpayer money on a project that massive in scope, Jarrard and county staff members claimed the implied authority to do practically anything and everything necessary to “bring the project to fruition.” It is ironic that it could have been Attorney Jarrard’s own failure to inform the individual board members of the legal problems with the Freedom Parkway admin site, early enough to halt the project’s momentum, that brought about the board’s decision to spend all that money in the first place. In which case, it could have been Mr. Jarrard’s own failure to inform the board at-large of the legal problems associated with the admin site, apparently violating his responsibility as the board’s legal advisor, that led to his proposed “implied authority” to go about various ways to fix the problems he might be at least partially responsible for creating, and could have possibly prevented, had he been more forthcoming. Was it truly an attorney-client relationship with a commissioner that kept him from disclosing that vitally important information to the rest of the commissioners before it was too late? Perhaps Mr. Jarrard owes Forsyth County taxpayers an answer to to that question.

Next, Commissioner Mills adds fuel to Mr. Jarrard’s hot seat, asking why the commissioners are paying the county attorney taxpayer money to draft resolutions for the City of Cumming to consider when the city has their own attorney?

Notice that in his statements Mr. Jarrard stood on certain presumptions county manager McKee established when he asked to speak first on the subject of the resolution. Remember, according to McKee the mayor was indifferent on where the county meets. That presumption of “mayor indifference” allowed Jarrard to claim that the resolution was “innocuous.” Given the interplay between the county manager and attorney, one should rightfully wonder whether both men worked together to create an impression that the city’s presumed “indifference” regarding the location the county does its business, created a legitimate reason to seek a city signature on Jarrard’s resolution, importantly, without the aid of any outside leverage that granting an easement request as part of a quid pro quo might provide.

Viewing the statements of the county manager and county attorney together, at the outset, county manager McKee presented a scenario essentially in which a “quid pro quo” deal would be virtually impossible. Shortly thereafter, in this last video county attorney Jarrard effectively took that baton from McKee and built his arguments on the foundation of assumptions McKee established, playing on the major assumption that the easement request was running in the background through the county approval system during the time Jarrard sent the resolution, the easement thereby having no relation to the resolution. McKee’s laid assumptions allowed Jarrard to maintain that the resolution was, “innocuous,” in other words, harmless to the city. And because it supposedly would not hurt the city to sign it, perhaps the city might just go ahead and do so, extending a hand of friendship across to those at the county who had recently burned them out of six million dollars. (Sorry, I couldn’t help myself)

So, this apparent dance involving the county manager and county attorney appears for all intentions to have been be choreographed prior to the meeting. There are substantial inaccuracies with each of their portrayals. The verifiable facts establish that the city’s requested easement was not simply a matter being worked on by staff in the background while McKee and Jarrard pursued a stand-alone resolution with the city. Therefore, the resolution was not “innocuous,” as Jarrard presented it to be. Had the resolution truly been “innocuous,” and had the city truly been “indifferent” to the location of the administration building, Jarrard would not have needed any additional persuasion, such as the prospect of granting an easement request, to obtain the city’s signature anyway.

In this final video of Mr. Jarrard’s remarks, the county attorney strains to argue a point that deals with Commissioner Mills’ question, but in the end he leaves her with no answer at all.

“Spiking the ball in the end zone,” if that is the way the county attorney chose to characterize the city response, should not have left Mr. Jarrard “curious.” Apparently, the county attorney would like the world to believe that some anomalous event, some circumstance for which there is no viable explanation, must have occurred over at the city for them to refuse such an “innocuous” resolution, change it to reflect their new feelings, and send it back. Apparently, Mr. Jarrard would like the world to believe he lives under a rock. To be brutally honest, changing the language and sending it back to the county signified a fundamental rejection by the city of the quid pro quo Mr. Jarrard proposed (using Attorney Kevin Tallant’s term), a deal which for some unknown reason, apparently neither the county manager, nor the county attorney want to admit proposing. Incidentally, a minute or so after Mr. Jarrard concludes, the audio of the meeting is apparently turned off. Just prior to that moment, Commissioner John suggests the county simply not follow the law, the only input Commissioner John would offer during the entire discussion, at least while the sound was being recorded.

Mr. Jarrard never mentions that he actually spoke directly to city attorney Kevin Tallant, does he? Perhaps if he did, he would be required to explain the true nature of that conversation, in which case anyone listening would naturally question the facts both McKee and Jarrard offered during the work session meeting. Perhaps those watching and listening would wonder whether the two corroborated on a narrative designed to hide the fact that during that phone call, Attorney Jarrard did in fact present the quid pro quo as described by Mr. Tallant, an “easement in exchange for resolution” deal, hoping to influence, or even coerce the city, needing that easement to a certain level of urgency, to sign the coupled resolution. That was the quid pro quo city attorney Tallant referenced during his presentation of the county’s resolution during the November 6 City Council meeting. Listen again:

If the resolution regarding the admin building location was truly “innocuous,” why would these two county officials try to hide the proposed deal from becoming public knowledge anyway? After all, as I wrote at the outset, it is doubtful that proposing a deal such as described would be illegal.

Apparently, what we are seeing is little short of desperation on the parts of certain Forsyth County personnel, the county attorney, and three commission members who voted for the admin project after being apprised of serious legal problems, some of whom, or all of whom, have been coordinating efforts to keep this public conversation from happening. Now we see apparently why. Those three commission members voted to take an exorbitant amount of taxpayer money, without asking the taxpayers, and spend it on what may be the largest project ever built with Forsyth County taxpayer funds, knowing that certain inherent legal problems impacted the project’s viability. Regardless what any of these players may try to tell you, the odds of allaying the legal problems associated with this site are extremely small, any general legislative solution opening the door for county governments across the state to desert their county seats in each of 159 Georgia counties. Such a change in the law would effectively remove the term “county seat” from the dictionary. During the events described above, the county manager and attorney gave their best efforts at drafting a resolution, dimly hoping to obtain the city’s agreement to ask the state delegation to sponsor the bills necessary to change the state law. They failed miserably and now depend on delegations from other, perhaps less dysfunctional counties, to take this ball and run it over what may prove to be an impenetrable goal line.

The Bottom Line

As attorney for the Forsyth County Commission, Ken Jarrard is charged with the responsibility to ensure the commissioners act within the law. It is his responsibility to ensure the commissioners have all the information they need to make decisions in keeping with the law. And it is his responsibility to warn the commissioners when the law would preclude them from executing plans the law does not allow. Apparently aware of legal problems associated with the chosen admin site in early 2023, and apparently saying nothing to the commissioners, possibly for an entire year, even up to the very night of the vote to fund a $114 million contract with taxpayer dollars, the evidence suggests that county attorney Jarrard failed to inform his clients of vital information he apparently had a duty to disclose, in a timely fashion, so as to prevent a mistake the magnitude of which could become hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars over the life of the project, which, as I describe, is the prospect county taxpayers are left to contemplate at this moment.

That said, nothing excuses Board Chairman Alfred John or county manager David McKee either, each who admitted knowledge of the legal problems bringing about these circumstances, and each who owed the entire board of commission members to have informed them of those problems in time to alter the gathering momentum as time grew near to the final vote.

In my opinion, and perhaps in yours, all of these public servants who aided in creating these circumstances need to go. And, frankly, this is what happens when the people give their government too much money. Decision-makers go rogue and squander such large sums on monuments to themselves. It is time to demand resignations. No more games. No more concealment. No more hidden agendas. Just leave, go, now.

Epilogue

Last Friday evening, 11 Alive News aired a story concerning the events and circumstances I relate in this article. The investigative reporter interviewed three local office holders, Commissioner Cindy Mills, Georgia Representative Lauren McDonald, and Cumming Mayor Troy Brumbalow, each who freely offered information to help relate the story. When 11 Alive contacted Forsyth County Government for comments, apparently no one would allow his or her name to be given during the segment, the county point of view on the matter offered in a written statement by an individual identified only as a “county spokesperson.” Here is the video that aired this past Friday evening.

Keep publishing, Sullivan.

You must be over the target. How do we know that? Because Forsyth County’s establishment doesn’t want you to publish.

We need observers, investigators, and writers like you in every county. Cockroaches abhor light. 🔦🔦Amazing reporting Hank.