The Theory and Meaning of America, Part 6

Analysis of the Case that America's National and Governmental Authority "Rebooted" With the Ratification of the Constitution

Note: To understand your place in the discussion here, please refer to the segments previously published in this series, and then review the segment entitled Part 5, the summary to date. This present segment assumes that the reader is brought up to date on the information that lays its foundation.

Analysis of the Proposition that America was Born-Again, Creating a New Basis of Sovereign Authority Under the Constitution

This segment of the series Theory and Meaning of America, will refute arguments cited in America’s elite law schools alleging that America essentially "rebooted" as a new and different nation under the Constitution, different than it was under the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation. To demonstrate the false nature of that argument, all one really needs is the language of the Articles of Confederation and Constitution, which conclusively denies it directly, and which also directly supports the truth that the United States of America today, is the same United States which existed under the AoC, and which existed under the Declaration of Independence. Furthermore, the Constitution certifies that conclusion and adopts it as the Supreme Law of the Land.

The argument that America rebooted its national sovereignty under the Constitution is grounded upon statements concerning the transformational “process” by which a nation was born in 1776, and by which that nation subsequently worked to craft an enduring national governing structure. Dr. Akhil Amar's (see parts 4 and 5 of this series) evaluation of the events and circumstances surrounding this “process” only deals with the “process” itself, as it progressed, rather than understanding in retrospect what the authors of the Constitution plainly intended, and documented as the outcome of the “process,” an outcome to which the affected parties in question would ultimately agree unanimously. Those parties documented their agreement to the final product of the “process” in Article VII of the Constitution itself, thus codifying the outcome as “supreme Law,” regardless of any particular “process” through which that outcome was determined.

Dr. Amar's argument finds its roots in the notion that the “process,” what he refers as the “process of ordainment” by which the goal of crafting an enduring government was ultimately accomplished (and agreed leaving no grieved parties), was not as “smooth” (my term) as required for this “final” emerging nation to have maintained its original national identity all the while this “process” was ongoing. And because the “process” was not as smooth as required by the standards he attaches to his analysis, then all of the meaning and historical significance that underwrites the Declaration of Independence is necessarily lost to the Constitution, relegated to remain forever simple poetry, prose from a bygone era, passé expressions of idealism from an extinct civilization, possibly no more significant to us today than the the nations of the Incas or Mayas.

Importantly, Dr. Amar’s interpretation of these matters is what today’s constitutional law students are learning.

In his book, America's Constitution: A Biography, taking the approach that Dr. Amar does, neither does he judge the overall results of this transformational “process,” nor does he judge the actual stated intentions of the Articles of Confederation, nor the intentions as stated and codified in the Preamble and in Article VII of the Constitution.

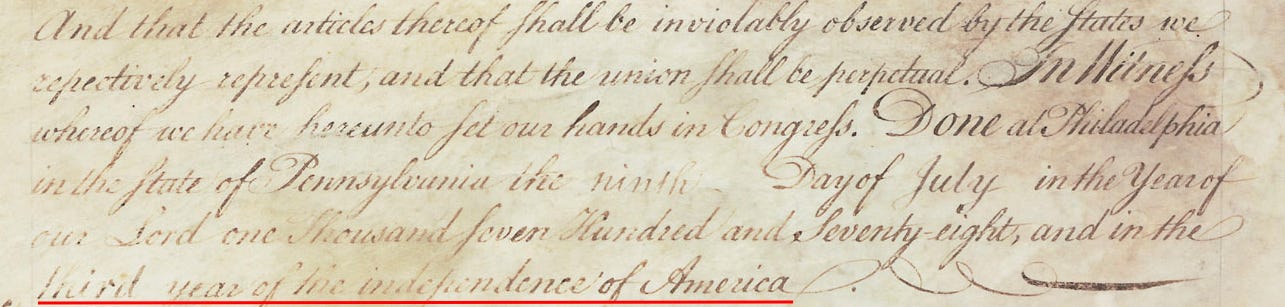

But conceding for the sake of argument, as Dr. Amar's analysis would require, that the authors of the Articles of Confederation, simply forgot to dissolve the nation created under the Declaration of Independence; and conceding, as his analysis would require, that the authors of the Constitution, neglected to mention, or therefore even possibly notice, that this “new” forming union would completely expunge the "old" union, and even conceding the remote possibility that these founders actually meant to void the agreement which begot the union already in place as the Constitution moved toward ratification, this much we know for certain: As of the date of the AoC's proposed ratification, those Articles express that the "United States of America," a nation, was in its “third year.”

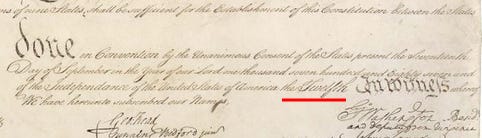

Carried with that expression, is a necessary implication that after the AoC's ratification, that nation would continue with the same national identity that existed since July 4, 1776. The Constitution’s Article VII certifies the presence of that implication, allowing that by 1787, as the authors of the Constitution moved to ratify that document, the same national body of sovereign authority known as the "United States of America" had been in continuous operation well into its "twelfth year," thus bridging the entire period of transition and governmental transformation between the dates of the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation.

And because the authors of the Constitution employed that very same time convention as the authors of the Article's of Confederation, the Constitution's Article VII necessarily implies an identical conveyance of a continuous national identity straight through the period of the Constitution, a document that declares being proposed in the "twelfth year" of the "United States of America." Because both the AoC and the Constitution use the very same time convention to document the respective dates of their proposed ratification, that language certifies that the nation existing under the Declaration of Independence, that same nation that carried over to the time period of the Articles of Confederation, would necessarily continue to operate under the Constitution and could in no authoritative manner morph into a “new” and different nation than had ever before existed.

But just to make sure that we give his position and fair chance, let's test Dr. Amar's theory against the language of the Constitution. According to this test, if his language is consistent with the Constitution, then it is a possible interpretation. If not, then it is not. If, upon its ratification, the Constitution’s authors had meant for America’s sovereign identity to die or to transform into some new animal, then why did they feel it necessary to state that the Constitution of this “new” nation was proposed in the “twelfth year” of some political entity that, if Professor Amar's theory is correct, had not existed for nearly nine years? Think about that. Because that theory does not make any sense with the clear terms of the Constitution, Dr. Amar's theory, and any conclusion that finds basis in that theory, cannot be correct.

In the next segment we will look at some very specific arguments used to bolster the case that America 'rebooted' under the Constitution, and demonstrate the errors in each. And then a little further into the discussion we will explore what some early statesmen, George Washington for one, had to say about all this at the time. After all, America’s first President under the Constitution should know.

So we will talk again soon...

Hank