The Theory and Meaning of America, Part 10

How the Dred Scott Decision proves the Constitution is not a standalone document

In the previous installments in this series, The Theory and Meaning of America, the case is building that the Constitution is not a standalone document. The Constitution is the final of a series of three documents, which together currently convey authority to the government of the United States. The Constitution tells us this, holding in its Article VII that the congress of the United States of America, proposed the new Constitution for ratification in the 12th year of the existence of the nation known as the United States of America. Arithmetic settles any question that the year in which the nation for which the Constitution came to be supreme law began with the signing of the Declaration of Independence in the year 1776. Because this is true, then all of the assumed truths laid out in the Declaration, which originally formulated the rationale resulting in the independence of those United States, are inherited to the Constitution. And for this reason as well, all national commitments and agreements occurring between 1776 and 1789, prior to the Constitution's ratification, remain commitments and agreements which must be honored under the Constitution.

One such committed agreement is the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which officially ended the American Revolutionary War. Under that agreement, “two nations,” the United States and Great Britain, acknowledge and submit to the authority of the Holy Trinity, God of the Bible including the New Testament. That reference to the authority of the Holy Trinity therefore recognizes the New Testament in its entirety, holds the New Testament as truly the Word of God, and holds one truth in particular, that being that all authority on Heaven and Earth is given to Jesus Christ (Matthew 28:18), as the New Testament plainly attests. Since all authority is given to Jesus Christ, then any authority for men and nations, if it is true authority, must first flow through Jesus Christ, and then from Jesus to men. As we will discover, that flow of authority is the same flow described in the Declaration of Independence. But we will speak more on that later in the series.

In part 9 of this series, we uncovered that Abraham Lincoln, America's revered 16th president, and George Washington, America's universally admired first president, both understood that the Constitution receives its authority from the agreements which precede it, the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. But Lincoln and Washington are certainly not alone in that determination. References to the principles of the Declaration of Independence abound, not only in the political rhetoric of the day, but also in constitutional questions coming about during the times these men lived.

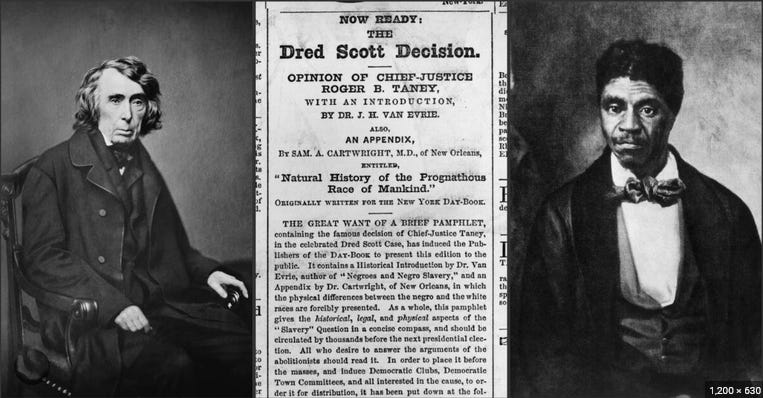

And in this installment in the series, I believe it is particularly instructive to look at one such constitutional case, opined by the United States Supreme Court, a case that helps to demonstrate that the Constitution is not supreme law in and of itself, but a law which can only be successfully interpreted when understood in the light of the conditional authority it receives from the Declaration of Independence, as conveyed to it through the Articles of Confederation. The case I cite here may seem a strange one to try to use to bolster a case that the Constitution receives its authority from certain ideals laid out in the declaration. That is because the ruling ultimately defied those ideals. But in the justice's rationale, the Declaration's authority over the question before the court is undeniable. The case in question is the Dred Scott Decision.

In the Dred Scott case, Chief Justice Roger Taney authored the U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that people of African descent brought into the United States and held as slaves (or their descendants, whether or not they were slaves) were not protected by the Constitution and could never be U.S. citizens. The court also held that the U.S. Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in federal territories, and that because slaves were not citizens, they could not sue in court. Furthermore, the Court ruled that slaves, as chattels or private property, could not be taken away from their owners without due process.

The rationale behind Taney's opinion finds basis in the chief justice's interpretation, not of the Constitution, but of all things, the Declaration of Independence! That's right, the Dred Scott case, which held that Negroes were NOT equal to whites, finds its deciding rationale in a document that extols the basic truth that 'All men are created equal." In the high court's opinion, Taney judges the facts of the case, and the law, in the light of the Declaration, ultimately finding that Negroes were “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Here are some excerpts from Taney’s opinion:

1) In the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.

2) The language of the Declaration of Independence is equally conclusive: It begins by declaring that, 'when in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and nature's God entitle them, a decent respect for the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.'

It then proceeds to say: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among them is life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.'

The general words above quoted would seem to embrace the whole human family, and if they were used in a similar instrument at this day would be so understood. But it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration; for if the language, as understood in that day, would embrace them, the conduct of the distinguished men who framed the Declaration of Independence would have been utterly and flagrantly inconsistent with the principles they asserted; and instead of the sympathy of mankind, to which they so confidently appealed, they would have deserved and received universal rebuke and reprobation.

Yet the men who framed this declaration were great men high in literary acquirements high in their sense of honor, and incapable of asserting principles inconsistent with those on which they were acting. They perfectly understood the meaning of the language they used, and how it would be understood by others; and they knew that it would not in any part of the civilized world be supposed to embrace the negro race, which, by common consent, had been excluded from civilized Governments and the family of nations, and doomed to slavery. They spoke and acted according to the then established doctrines and principles, and in the ordinary language of the day, and no one misunderstood them. The unhappy black race were separated from the white by indelible marks, and laws long before established, and were never thought of or spoken of except as property, and when the claims of the owner or the profit of the trader were supposed to need protection.

3) What the construction was at that time, we think can hardly admit of doubt. We have the language of the Declaration of Independence and of the Articles of Confederation, in addition to the plain words of the Constitution itself; we have the legislation of the different States, before, about the time, and since, the Constitution was adopted; we have the legislation of Congress, from the time of its adoption to a recent period; and we have the constant and uniform action of the Executive Department, all concurring together, and leading to the same result. And if anything in relation to the construction of the Constitution can be regarded as settled, it is that which we now give to the word 'citizen' and the word 'people.'

In each of these three paragraphs of Taney's opinion, the chief justice repeatedly invokes the principles of the Declaration of Independence. He even invokes the language of the Articles of Confederation. Thus, obviously, in order to faithfully interpret the Constitution, and sustain his arguments, Chief Justice Taney felt it necessary to reconcile his Dred Scott rationale, not only against the relatively low standards of the Constitution, but also against the much higher standards of the Declaration of Independence, and even the general language of the Articles of Confederation. But if the theory that the Constitution is a standalone document is correct, the Declaration of Independence speaks to an entirely different nation than the one who’s supreme law is the Constitution. And the Articles of Confederation pertains solely to a 'multi-lateral treaty organization' that would have nothing whatsoever to do with the United States of America, a nation under the Constitution. That being the case, knowing that there is no flow of authority between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, Taney would have had no reason to justify his opinion against the principles of the Declaration of Independence, much less invoke the Articles of Confederation. In so doing, Taney went miles out of his way and made his job exceedingly more difficult.

There is only one explanation for Chief Justice Taney choosing to justify the Dred Scott decision against the principles of the Declaration of Independence rather than simply the language of the Constitution. And that is that the without the Declaration of Independence serving as its source of authority and its guide for interpretation, the Constitution is a relatively meaningless arrangement of rules without reasons. Taney understood the authoritative nature of the declaration. He understood that anything less than justifying his opinion in the light of the Declaration would be questionably authoritative. As poorly as he interpreted those documents, Taney’s Dred Scott decision plainly demonstrates that Chief Justice Taney understood that the Constitution derives its authority from a rationale of principles, expressed as they are, in the Declaration of Independence.

Ironically, only by citing the Declaration of Independence, and bastardizing its meaning, did Taney feel he could overrule what that document plainly states.

So even a bastardization of the meaning of the Declaration of Independence helps to shine the light of truth on that same meaning. That is the nature of truth. Truth cannot be hidden by falsehood. And the truth is that the Constitution of the United States draws its authority from the Declaration of Independence, through the Articles of Confederation. So if it can be conclusively demonstrated that those earlier documents derive their authority from God of the Bible including the New Testament, then it is unavoidable that even today, the Unites States of America is truly one nation under God, and draws its authority from Jesus Christ, Who as the New Testament proclaims, owns all authority in Heaven and earth.

This installment ran just a bit long. But it had to all be laid out. In the next installment, knowing what we now know about the flow of sovereign authority from the Declaration of Independence through to the Constitution, we will begin to explore the declaration and find out just how the authority for the United States of America came to be.